Cheap Trick – I Want You To Want Me

Bands are always evolving, often due to personnel changes (there are at least three clearly distinct versions of Fleetwood Mac (the Peter Green, Bob Welch and Nicks/Buckingham eras), a solid case can be made for two others, and there are arguably several more beyond those, and Pink Floyd’s sound has been likewise defined by the three men who took turns fronting the group) but sometimes due to the existing group maturing together or becoming interested in new sounds. This can be difficult for listeners to accept – music fans are notorious for becoming attached to a version of the artist that they first fell in love with and refusing to follow them as they veer in new directions. I have a friend who seems to always prefer a band’s first record: I’m not sure there’s any artist I can say that about.

One such band that evolved in an unexpected direction was Cheap Trick, and about the only explanation for this is money. Between February 1977 and April 1978, the band released three albums of original material, with negligible sales figures as the last of these peaked at number 48 on the albums chart. Singles success was similarly evasive: only one release – the all-time great tune “Surrender” – made the charts, stalling at number 62. Critics, on the other hand, loved Cheap Trick: 1977’s “In Color” ranked 10th in that year’s Pazz and Jop poll, and “Heaven Tonight” was number 22 the following year. Some critics went so far as to compare them to The Beatles, which is a simply awful thing to do to a young band (except Klaatu – those guys were asking for it). This acclaim was one of the more unexpected discoveries for me when looking over old Pazz and Jop lists, because my contemporaneous experience of Cheap Trick was of a band that no one took seriously, including the band members themselves, which was a big part of their charm.

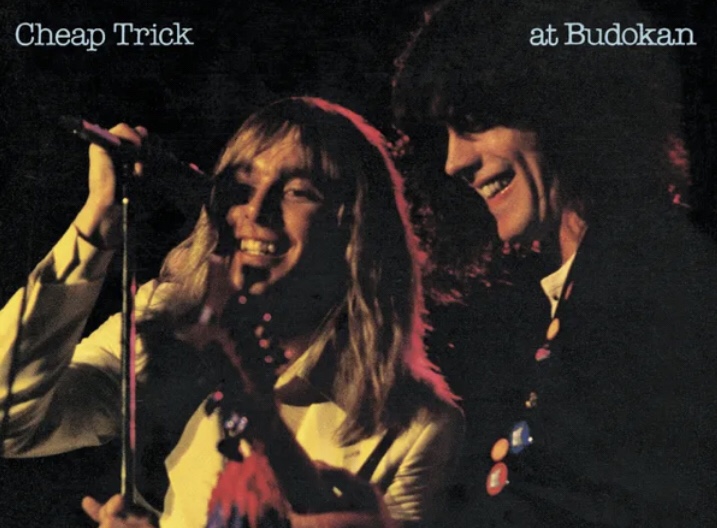

Another funny thing was happening across the Pacific Ocean. While North American listeners mostly shrugged at hearing these punkish power poppers, young folks in Japan went nuts: their 1978 tour was greeted with paroxysms of Beatlesesque proportions. A few of the shows at the Budokan arena were recorded for what was initially intended to be a Japan only release. Pressure mounted to share it with the band’s home audience, and in April 1979, “I Want You to Want Me” exploded onto our radios.

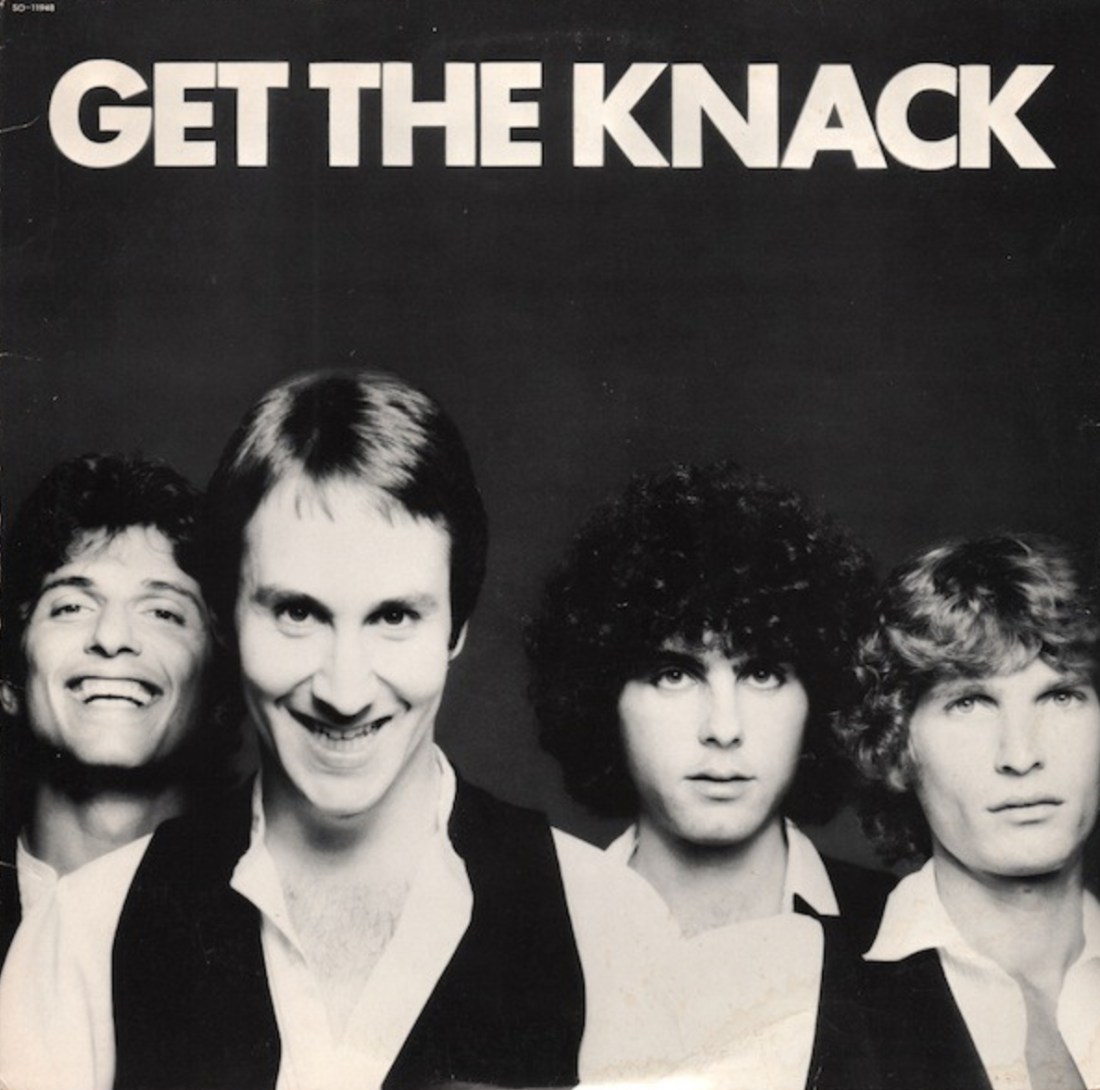

Some context, for those who either don’t remember or are too young to have been there. The first few months of 1979 were still the heyday of disco, and a glimpse at the songs that made Billboard’s top 10 singles list over the first third of the year shows a lot of this genre paired with a plethora of soft poppy tunes. About the closest thing to a song that really rocked during that period had been “Hold the Line” from Toto – never a good sign for a rock fan. (I will explain elsewhere why songs like “Sultans of Swing” and “Heart of Glass” don’t count.) Matters were so dire that Frank Mills’ “Music Box Dancer” reached number 3. It was indeed a very dark timeline.

So, a song like “I Want You to Want Me” was musical Viagra to all the hormone-drenched teen wannabes sweating away their bewildered frustrations with a musical ecosystem that didn’t seem to have a place for them. It blasted out of the speakers with the confidence you would expect from a much more successful band – it’s hard to argue with 15,000 screaming Japanese girls as an ego boost. And it was made to be played loud, with Rick Neilsen’s swirling guitar and Bun E. Carlos pounding the living shit out of his drum kit. But these were the (not conventionally attractive) faces on the back of the record’s jacket: on the front were the more adorable faces and flowing locks of lead singer Robin Zander and bassist Tom Petersson. The combination of cutie pies and loud noise made for a four quadrant blockbuster, with the album going on to eventually sell over 3.5 million copies in North America.

After Zander emphatically states the song’s title, Carlos goes a bit nuts on the drums, then the guitars jump in with a riff that I will recognize long after my inevitable dementia sets in. While Zander sings, Carlos thumps away as little swirls of fuzzy guitar slide up and down. On the original release in Japan, the song topped the charts, so the audience knows when to sing along: you can hear them in the break between each of Zander’s “Didn’t I, didn’t I” lines, and it’s kind of awesome. Nielsen finally gets a moment at 2:11, but it feels like a cheat when the singer jumps back in before he can really get rolling. Worry not: his real moment to shine comes at 2:29, and the bedroom rock stars are given 10 seconds of dreamy air guitar inspiration. The pace is brisk for three minutes, followed by a brief respite to bask in their fans’ love (though the audience is unusually muted at this point – were they dazed after all the screaming?), before winding down in a squall of guitars and drums. Perfection.

The original version is ranked the 1372nd best song of all time on Acclaimed Music, which may not seem that impressive until you look just below that and see greats like Peter Gabriel’s “In Your Eyes” (1374), The Beatles’ “She’s Leaving Home” (1379) and “Let’s Go Crazy” by Prince and the Revolution (1380). While the band went on to have other hits, including a number one with the 1988 power ballad “The Flame”, they were by then a more conventional rock band, and none of these received the kind of love from critics that the early records got. Carlos left the band in the early 2010s in a nasty breakup, but the other three carry on, occasionally with Zander’s son helping out, with their most recent album (an often catchy collection – I was especially taken with “Boys & Girls & Rock N Roll”) being released in 2021. Their next scheduled show is at Soaring Eagle Casino in Mount Pleasant, Michigan on December 6, and based on recent set lists, there’s a near 100% chance that “I Want You To Want Me” will be played. Screaming Japanese teenagers are probably not included, of course. Probably.