Jim Croce – Bad, Bad Leroy Brown

As much as I love listening to music, as well as talking and writing about it, I am bereft when it comes to creating it. Junior high school music classes included playing the ukelele and recorder, I once owned a keyboard (officially purchased for my children, but, sure, I had notions, too), and I have made several attempts to learn the guitar, but always lacked the staying power to see it through. It may be that my destiny was to end up exactly where I am.

My first glimpse of how I might not be up to swimming in the musical deep end came in the spring of 1976, when I was 11 years old. I had made some early attempts at songwriting by then, if you can call it that, since it consisted of lyrics with a melody, but not even rudimentary chords. I was not shy about promoting my efforts, so on a school trip to Ottawa I broke out some of my songs and sang them for classmates. I remember only positive responses, because of course I do, and I at a minimum felt bolstered in my delusions by that positivity.

Also on that trip was Robert Barrie, who was one of my closest friends. I expect I had heard him sing before that point, but have no firm memory of it. But on the train back to Nova Scotia, he sang for our group, and I remember that as clear as day. It was a lightning bolt through the heart, with their enthusiastic response letting me know just how far I had to go if I was serious about making a life in music. I had dreams, but Robert had actual talent, and all else being equal, you’re far better having the latter. Luckily for me, as the years since have proven, I wasn’t serious about making music; rather, it was one of many dreams (professional hockey player being one, film director another – aim high, right?) that I was trying on over the journey to whatever the heck you want to call what I’ve done with my working life. Robert, on the other hand, was serious, and he has continued to play music in one capacity or another to this day.

That trip came back to me a few weeks ago on a visit to Cape Breton to celebrate the lives of my recently passed mother and stepfather. Robert and I are still close, and when we learned he’d be playing a few solo shows during our visit, my wife and I made up our minds to see him. It turned out to be a fortuitous evening: he was playing at the very place (rebuilt after a fire) where my mother and stepfather first met over 40 years ago, and the evening included a surreptitious request by our future son-in-law for permission to ask our daughter to be his bride. (So old fashioned!) And one of the songs he played during a fantastic show was Jim Croce’s “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown”: the very song that he sang on the train that had left me breathless with jealousy over his colossal talent. To add to the fortuity of it all, he had only recently added it to his set list.

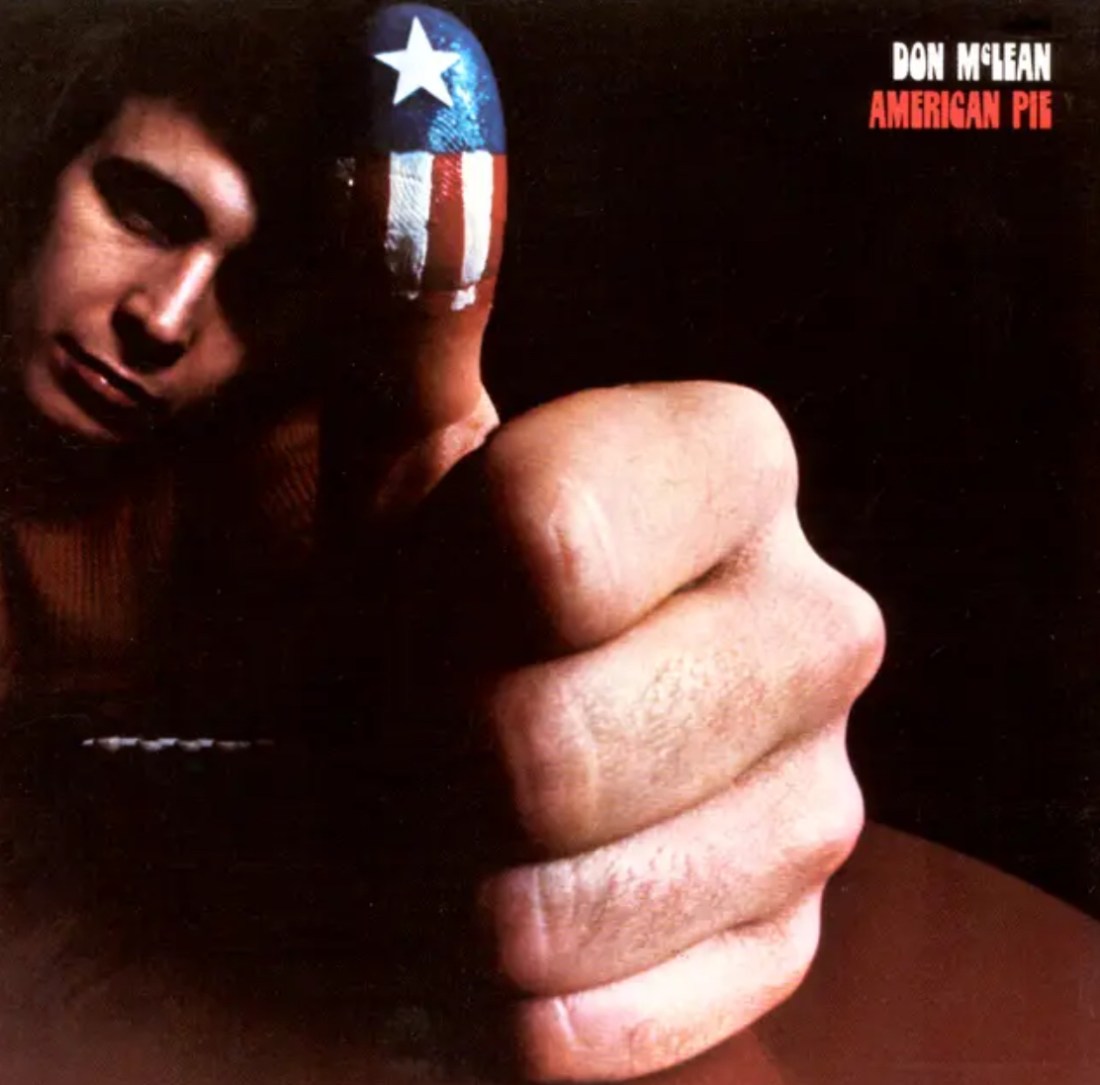

Of course, you know the song: it was a number 1 hit in 1973, and will remain a staple of oldies radio stations as long as such things exist. Croce, tragically, never got to see this afterlife for his song, passing away just two months later and joining the far too long list of musical greats who died in an aviation-related incident. (There’s a Wikipedia entry for this, for God’s sake.)

It starts with a rollicking honky tonk piano, which is either inspired by or stolen from (depending on how generous you feel) the opening to Bobby Darin’s “Queen of the Hop”, and there’s a big “Woo!” before the opening verse kicks in. It isn’t a complicated song: the pace never really changes, and other than a bit of noodling on the guitar and piano starting with the second verse, nothing much happens in the background of the tune. As for the lyrics, Croce never says that Leroy is Black, but he certainly sounds like a character out of a blaxploitation flick: fancy clothes, big flashy cars, a penchant for criminal activities, certain linguistic clues. Leroy is not only the bad guy in the story: he loses the climactic battle. So, it’s basically the tale of an asshole who gets his comeuppance. Of such ingredients are chart topping hits cooked up.

When my father passed away in February 2007, I knew I wasn’t going to be getting any part of an estate, but there was something I wanted. After the funeral, I was trying to figure out how to ask my stepmother for his old Fender guitar, but she offered it to me unprompted. It followed me to a new home a year later when my first marriage broke up, staying in its case until my future wife bought me lessons as a Christmas present. I was working out how to play “Too Much” from the fantastic Elvis Presley compilation “Elvis 56” when I was accepted into law school, and back into the case it went. 15 years later, it’s still there.

In 2024, during one of my many visits that year to see my dying mother, my Uncle Jimmy, who was present when I was gifted that guitar, asked if I ever played it. I confessed that I did not. This was one of two times that year that I believe I disappointed him. I corrected one of those on this last trip, when I finally visited my father’s gravesite for the first time. I think it might be time to crack open the guitar case and get to work on the other. It’ll just be for me and my dad – and Jimmy, if he’s okay with me not sounding as good as Robert, or my father, for that matter. We can’t all have talent, but that’s no reason not to do the things we love.