Peter Frampton – Jumpin’ Jack Flash

So, yeah. Peter Frampton. Let’s start there.

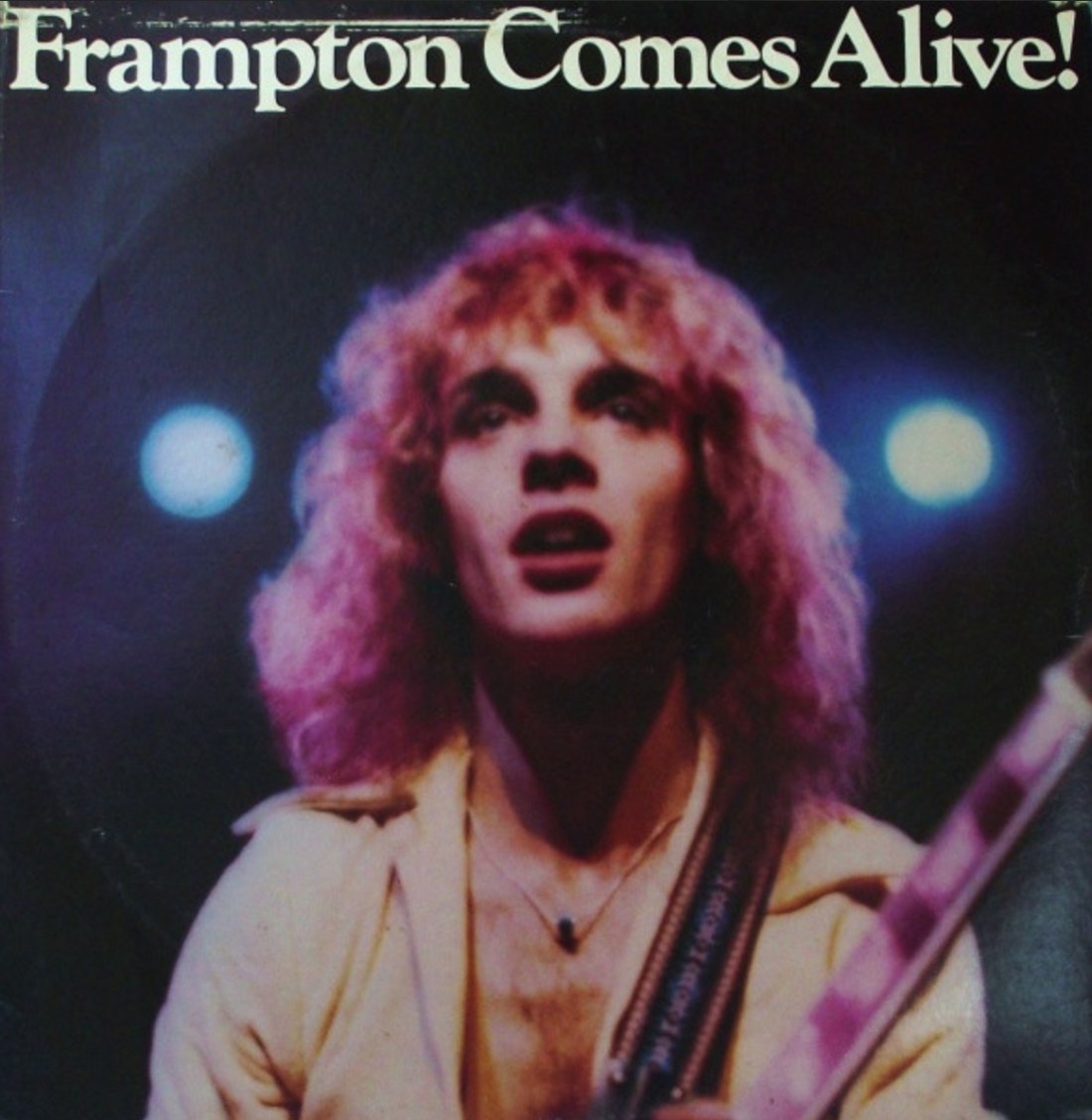

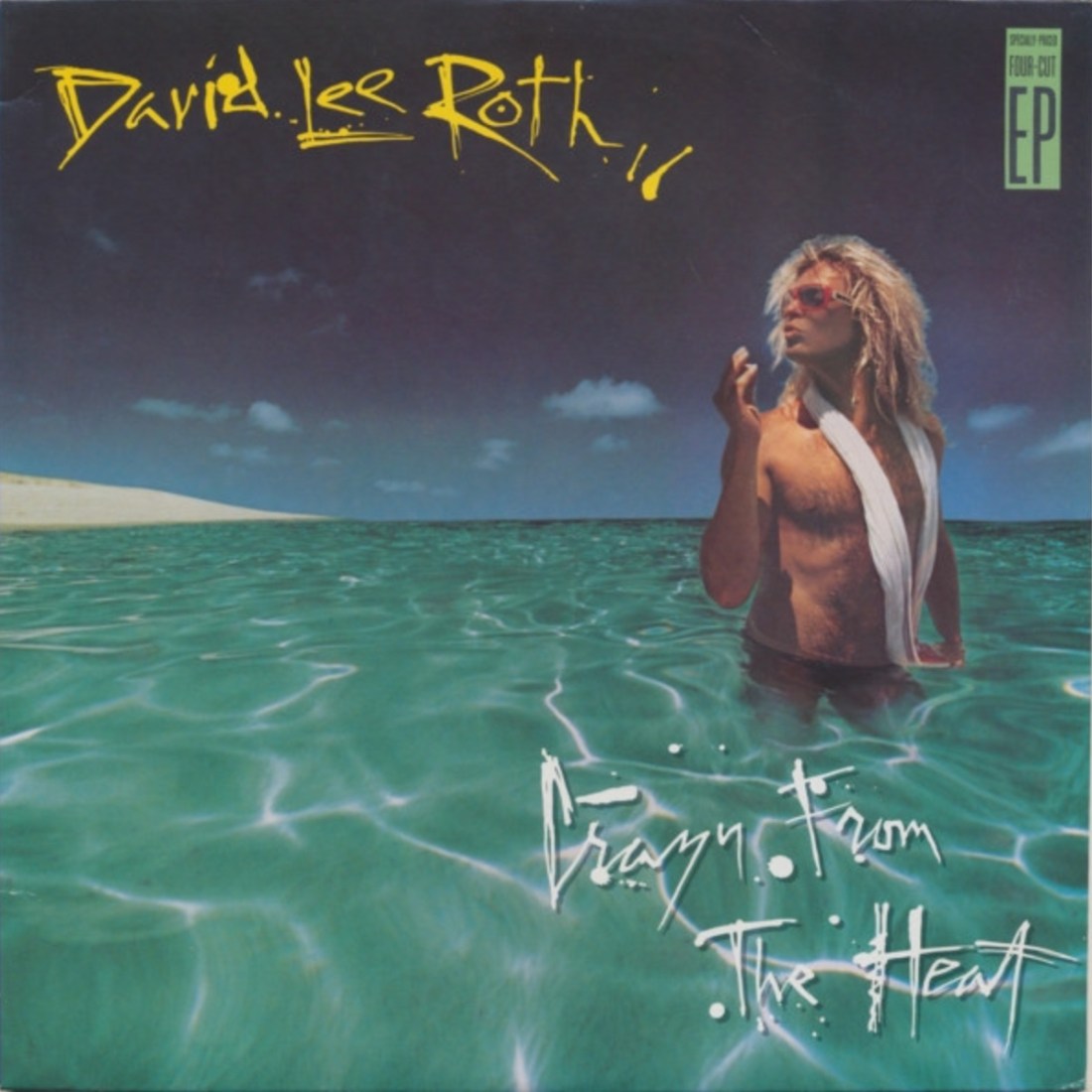

In 1976, for reasons that are not clear in hindsight and probably didn’t make a lot of sense at the time, A & M Records released “Frampton Comes Alive!” The question is why Frampton, after four albums and only modest commercial success, was deemed worthy of the double live album treatment. Clearly, someone at the label was at the top of their game because the record was a true sensation, selling around 10 million copies and producing three hit singles. Buried in all the hype was, at the end of side three, a cover of “Jumpin’ Jack Flash”. And though I read the liner notes and knew it was a Rolling Stones song, it may as well have been a Frampton original, because I had never heard the Stones’ version. I don’t know how that could have happened but it did, and that made it – still makes it – a Peter Frampton song for me. (I also never heard “Tumbling Dice” until it showed up on the “FM” soundtrack as a Linda Ronstadt cover in 1978. Someone older than me clearly fell down in not turning me on to the Stones.)

The album still kicks ass, especially the 14:15 long “Do You Feel Like We Do” and the guitar lick at 3:04 and 4:20 of “Something’s Happening”, and Frampton, now in his 70s, remains one of the coolest guys out there. His Twitter feed is a frequent delight, though it helps that we tend to agree on political and social issues.

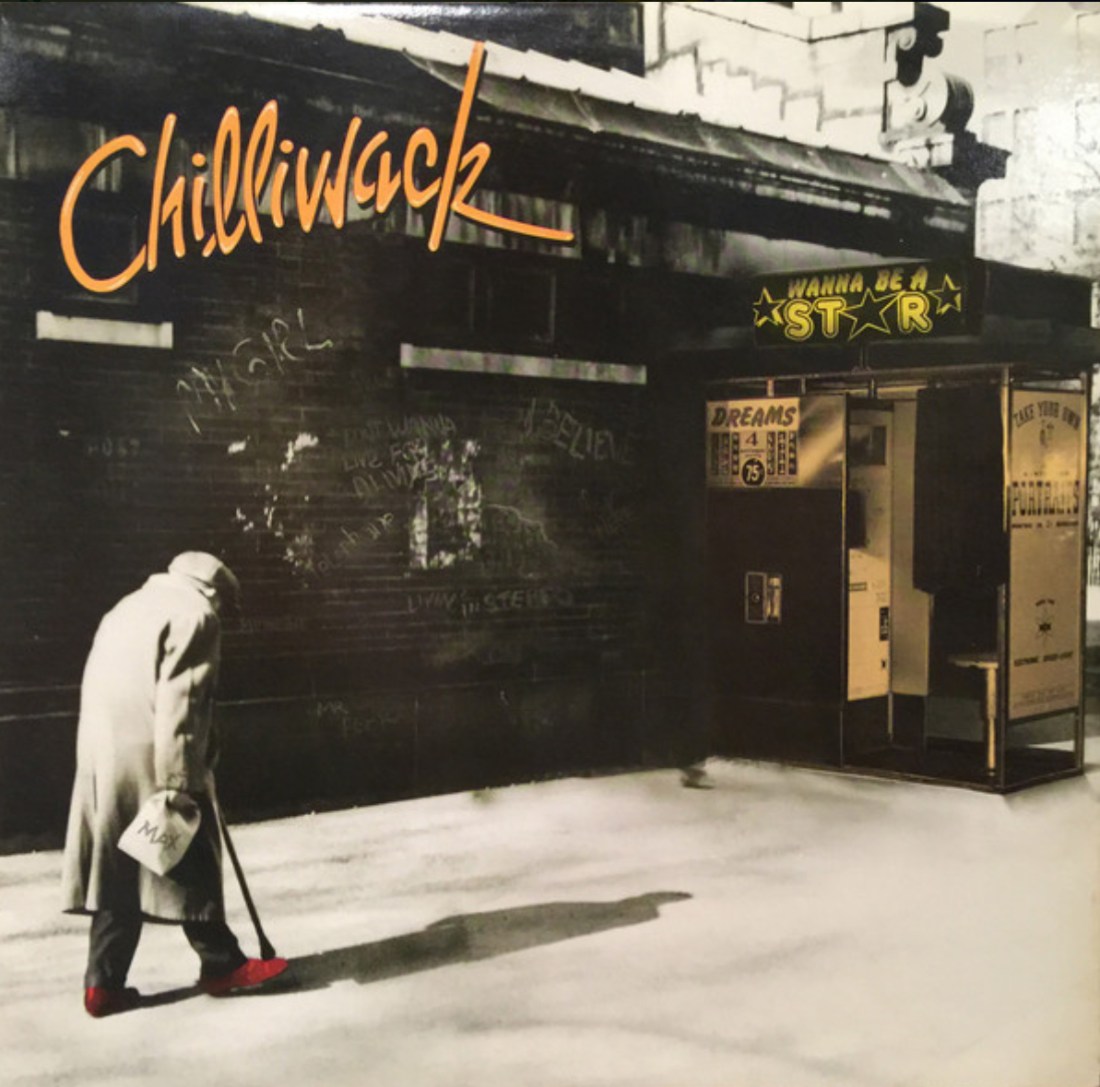

With that out of the way, let’s get to the crux of this: every teenage boy wants to be a rock star. Okay, maybe a few don’t, but they all have equally preposterous alternate goals. It doesn’t matter if you can’t sing or play an instrument: in your bedroom, you’re a rock ‘n’ roll god. And it never really goes away: even at 58, you can at times find me in my kitchen at 5:00 a.m. supporting Tom Scholz with some wicked air guitar licks on “More Than A Feeling”.

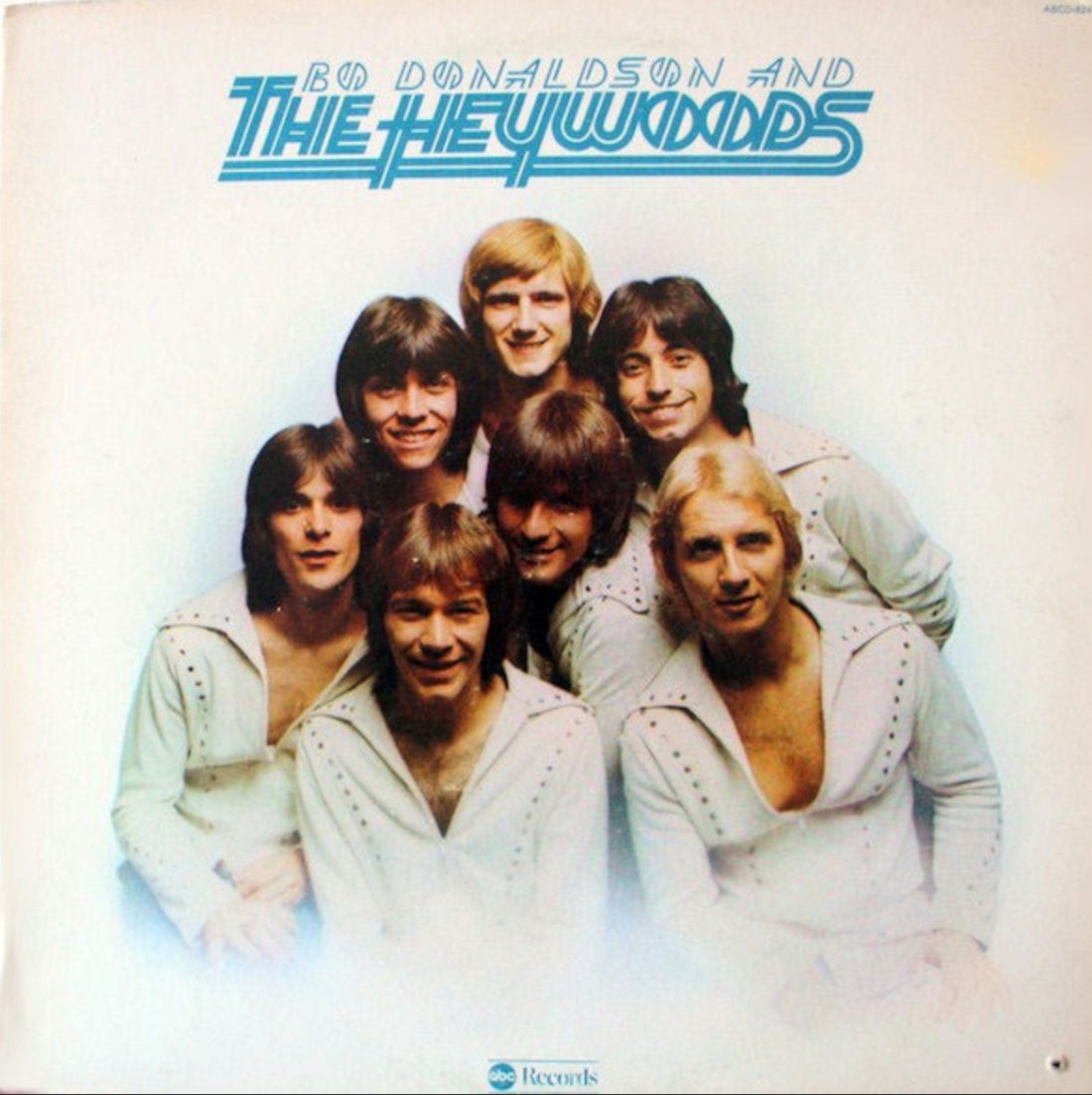

I actually had friends who sort of were rock stars in our community. Robert Barrie and Alan Sutherland were two of my pals in high school, and they played together in a series of bands, even releasing a pretty cool single when we were in Grade 12. (Shout out to “Endlessly” backed with “Coke Avenue”, though I was always a “Kiss Your Picture” guy – you can’t beat a good power ballad.) I haven’t seen Alan in ages, but Robert’s house has always been a guaranteed stop on my rare trips back to Cape Breton. I can’t remember if they were still playing together, but when my rock star moment came, Robert was the one who made it happen.

It was summer, I’m pretty sure 1985. I was back in Cape Breton for a visit, as were some other old friends – definitely Doug Maxwell (R.I.P., you magnificent bastard – BTW, if you don’t get that that was a compliment, I can’t help you), almost certainly Sandy Nicholson, probably Darrell Clark. Robert’s band was playing a charity event and our gang went out to support the cause, of course, but mostly to drink cheap beer, try to win a raffle and see our friend play. Towards the end of the night, Robert called Doug to the stage, and, somehow thinking it was intended for all of us (it really wasn’t), the rest of our group followed, and before I knew it we had become an impromptu backing chorus on “Jumpin’ Jack Flash”. I learned that night that years of bedroom listens didn’t mean I knew the lyrics very well. I can’t remember what I thought was being sung, but “It’s a gas! Gas! Gas!” was not it.

It’s important to understand that I was born to be a backup singer. I would have made a great Pip, had I but only found my Gladys Knight. I can carry a tune, only sound good as part of a group, and am generally happy just to be included. The synchronized dancing would’ve been a challenge, but we’d have worked it out – it’s not like those guys were channeling James Brown or anyone equally electric. So that night, for the four or five minutes we were on stage, was glorious.

Oh, and Peter’s version? It’s good, but the original is so much better. There is, of course, no shame in that – they’re The Rolling Stones, for god’s sake – and I imagine Frampton would agree. Like all live versions, it seems, it goes on forever – twice the length of the Stones’ original. The original is a true strut song: crisp, with a propulsive backbeat, deep bass notes and a rich chorus. Frampton’s version is slightly sluggish, more plodding – more of a guitar god record than the singer’s showcase of the original – and stretched out for audience interactions.

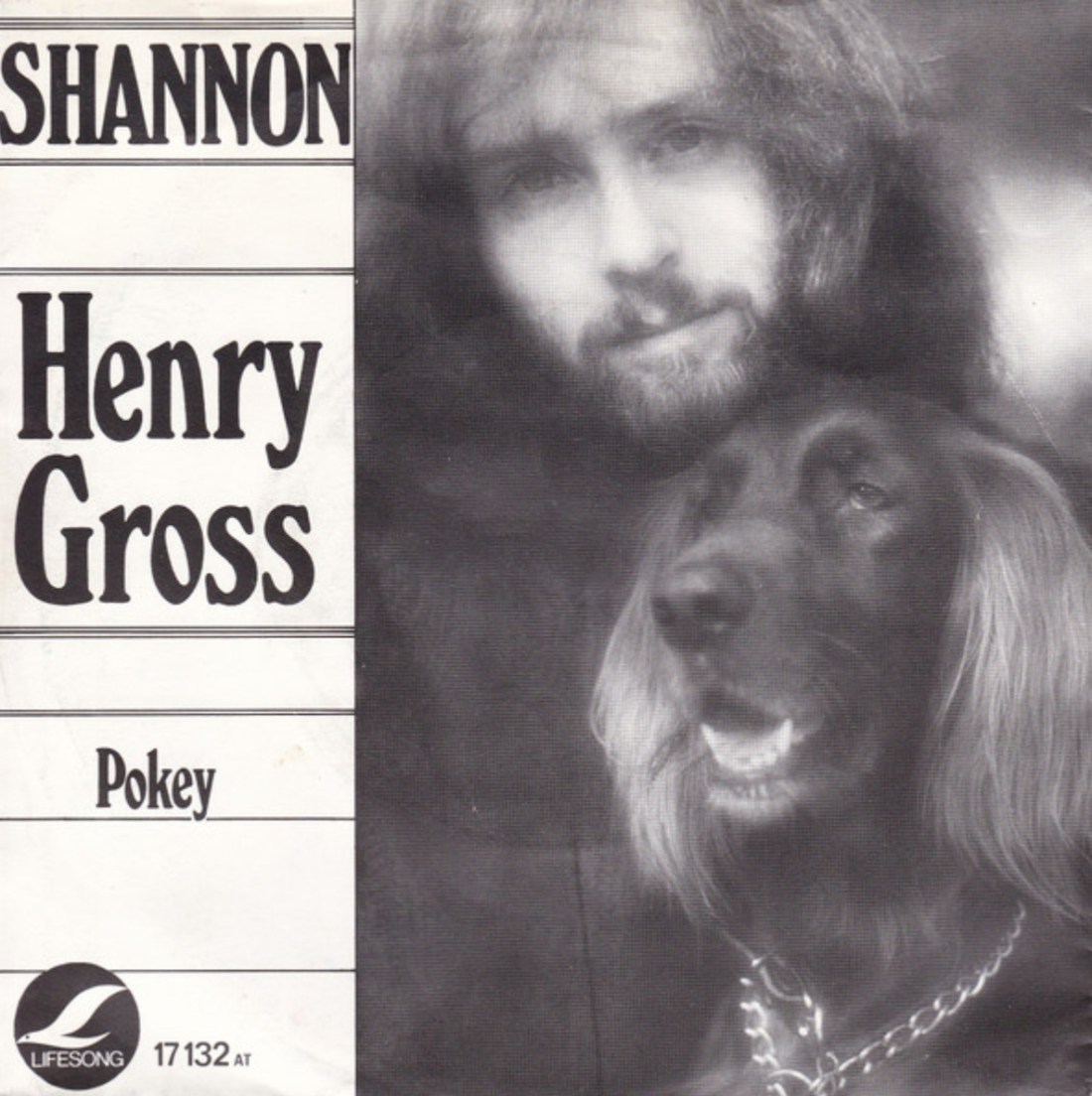

All of this is part of why I love cover versions: every few years, sometimes longer, a new group of people gets to call a song their own. My “Hurt” is by Johnny Cash, but yours could be Nine Inch Nails’ original. Your “Always on My Mind” could be by Elvis or Willie, while mine is by the Pet Shop Boys. Versions of “Hallelujah” are like Tim Hortons – there’s one for every block in Canada. There’s no right or wrong answer here: it’s whatever makes you fall in love with the song.