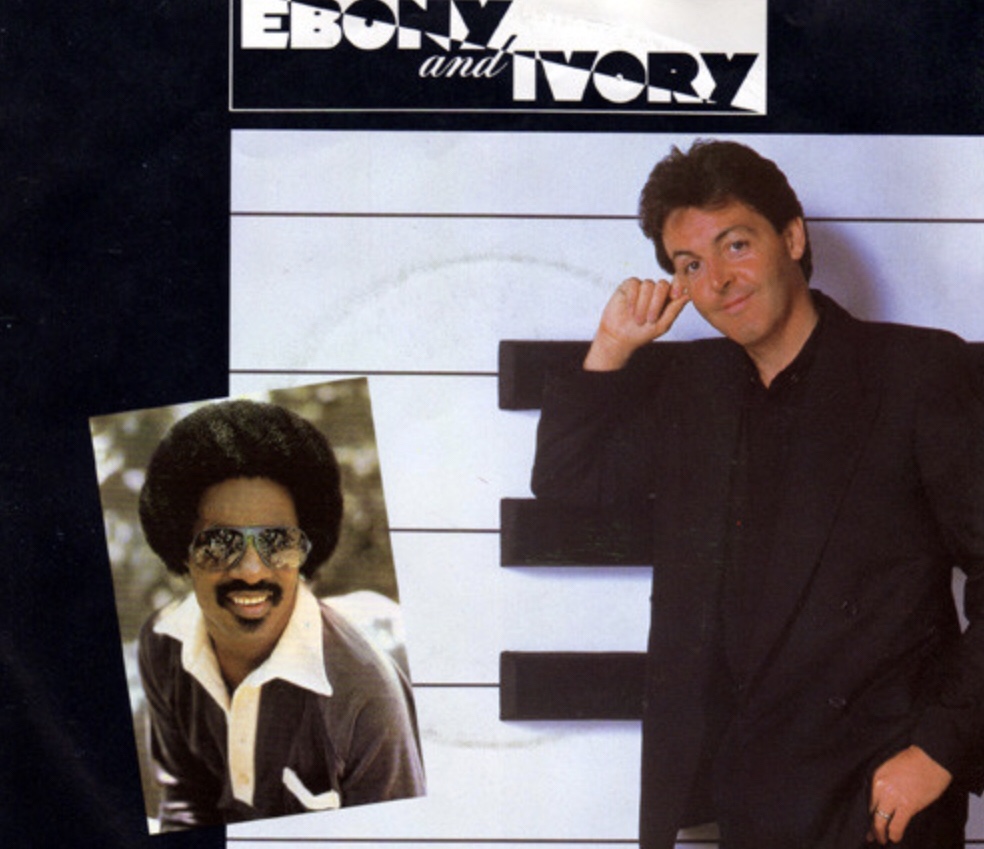

Paul McCartney featuring Stevie Wonder – Ebony and Ivory

It’s not surprising that our tastes change over time. When I was a teenager, I loved the novels of Irving Wallace. They were big books full of facts about fascinating topics: the Bible, the Nobel Prizes, American politics. Wallace was a capable but not particularly dynamic writer, and eventually I moved on to more challenging reads.

Those earlier loves can be enduring for nostalgic reasons even if our aesthetic sensibility no longer finds them pleasing as art. I recently listened to an album from The Ravyns, an early ‘80s band that had a minor hit called “Raised on the Radio” off the “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” soundtrack. The entire time it was playing, I just kept thinking that it was a perfect example of the overproduced faux rock of that era. I was trying to figure out what artist their sound most reminded me of, and then it hit me: Rick Springfield. Who I owned five albums by and listened to regularly into the early ‘90s without even once thinking that it might be shite. Who I still sort of love, but am now a little anxious about listening to very closely given my realization that his music may be sort of garbage and I think I’d rather not confirm that. Awareness can be a burden.

I mention all this because I am grappling with a question: why did 17-year-old me love “Ebony and Ivory”? Because 59-year-old me, and most intervening versions, wants all physical and digital traces of this song to be locked in a vault, dropped into Marianas Trench, have an anvil land on it Wile E. Coyote style and then blow the whole thing up for good measure. I don’t understand why we didn’t think it was awful at the time. I remember having a conversation about the song with my friend Alan Sutherland, who took his music very seriously, and he neither mocked it nor mocked me for liking it (and Al was always up for a good mock when circumstances called for it).

I had not really paid attention to it in years, and then suddenly there it was, in my poor ears, as the third track on a Paul McCartney compilation called “All the Best”. No, not even close to one of his best (though when “Silly Love Songs” also makes the cut, you know the bar is limbo champion low). Not when that record did not include “Helen Wheels”, “Maybe I’m Amazed” or “Mull of Kintyre”. Not when it could have been replaced by pretty much any omitted track from “Band on the Run”. No way.

So, why do I – the “there is no bad music” guy – think this song is so awful? First, is there a more treacly song out there? Yes, of course – the musical excrement that is “Butterfly Kisses” immediately comes to mind, and the name Bobby Goldsboro can give me hives. (I won’t link to them – if masochism is your game, you can easily find them yourself.) Neither of them, however, topped Messrs. McCartney and Wonder on Blender’s list of the 50 worst songs ever, where “E & I” ranked 10th. (“We Built This City” topped (bottomed?) the list, and I think everyone can agree – even, as it turns out, the woman who sang it – that it truly blows. (Aside: I just learned this was co-written by Bernie Taupin. How is such a thing even possible?))

Not a moment in the song isn’t sparkly clean, honed to a version of perfection that overlooks the part where a song should maybe be a bit dangerous to be actually fun. It’s all so artificial, a synth heavy soundscape that feels very lush, like lying in an aural down bed. There really isn’t much happening here: the only musically interesting bits are coming from Paul’s bass. It’s music for washing the dishes, not listening to, and thus is more akin to what is happening now than to an era where you still had to pay attention to the music coming over the air lest you miss something great and never have a chance to hear it again. “E & I” is musical wallpaper, and, like all wallpaper, if you look too closely you’ll notice the torn edges, the parts that don’t line up quite right and the soul crushing blandness of the thing. That’s this song in a nutshell.

I don’t doubt that Paul and Stevie believed in their message, limited as it may be to the confines of a chorus and a single repeated verse. The song’s notions about racial harmony were belittled on release as simplistic, and it’s not like another 40+ years of people trying to destroy each other on the basis of ethnic differences has redeemed their poptimism. But that never really concerned me: I knew exactly two Black people, and while race may have been something the two of them were highly conscious of, I wore blackface in our high school musical “Finian’s Rainbow” and never gave it a moment’s consideration. (I was 17 and living in a less enlightened time and place – the adults in the room maybe should’ve thought a little more carefully about the show they selected that year for a bunch of white kids to perform. Those photos could damage my political career!)

McCartney and Wonder made tons of music that I love, but very little of it came after this team-up: Stevie’s last widely acclaimed album was 1980’s “Hotter Than July”, and some feel this song marked the point where Paul began to lose credibility as an artist. You have to give them credit for one thing: it takes a lot of confidence to make a record this earnest, although no one ever went entirely wrong recycling lame messages about humanity’s inherent goodness. The lyrics were made for a United Nations banner, not the top of the charts, yet somehow that’s where they ended up. I guess we were just really boring in 1982.